Project Description

Schattenrisse/Silhouettes. Zeichnungen und Objekte

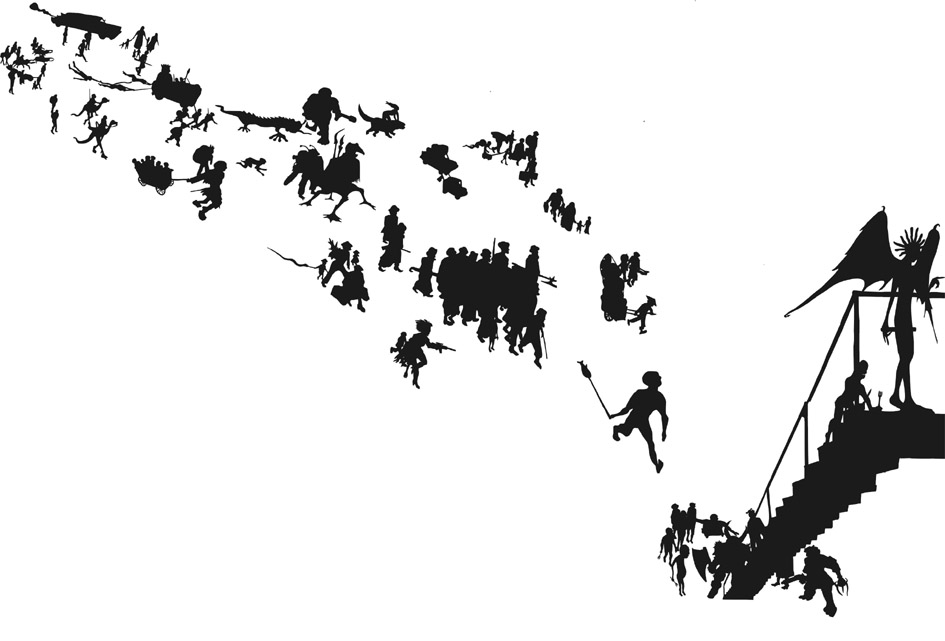

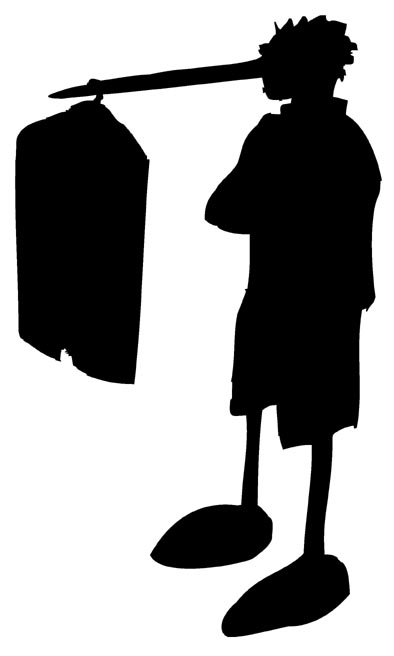

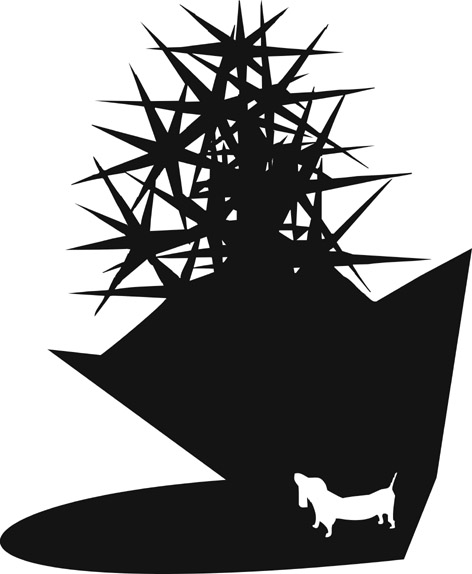

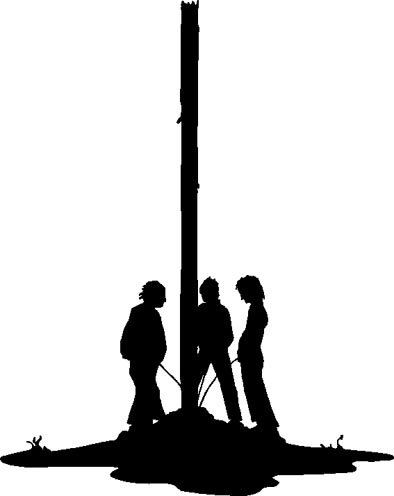

Schattenrisse als Einzelmotive entstehen als Zeichnungen oder entwickeln sich aus komplexeren Wandbildern. Sie werden häufig als Sperrholzeditionen / Auflagenobjekte herausgegeben. In der Form ergeben sich auch narrative Arrangements, in denen die einzelnen Schatten erzählerische Versatzstücke sind.

|

Wenn der Hirsch raucht

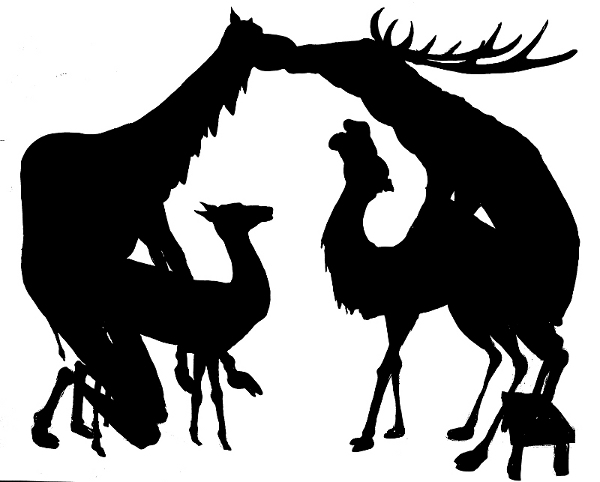

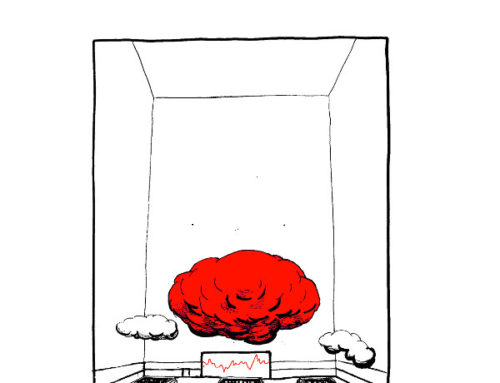

Der Text wurde usprünglich im Katalog von 2005 publiziert, (Bezieht sich zentral auf die Schattenboxen, Kästen die Silhouetten auf mehreren Ebenen enthalten) Der Schatten ist die Aufhebung der materiellen Beschaffenheit des Körpers und zugleich unabdingbarer Verweis auf seine Existenz. Schon in den umrandeten Handabdrücken steinzeitlicher Höhlenmalerei drückt sich die Vorstellung aus, dass die Fixierung der menschlichen Umrisse mehr als jedes gemalte Bild die Erinnerung an einen Abwesenden bewahre, gleich einem Abdruck seiner physischen Präsenz. Henrik Schrats Schatten verbergen hinter ihrer Oberfläche weniger schockierende Momente als vielmehr eine bemerkenswert leichtfüßige Erzählkunst doppelter Böden und hintergründigen Humors. Seit einiger Zeit entstehen große kastenartige Objekte aus Holz, Papiertheatern ähnlich, die die erzählerische Wirkung seiner Scherenschnitte ins Bühnenhafte steigern. Auf der Lichtung im Tannenwald begegnen sich, den Bildvordergrund diagonal durchschneidend, ein röhrender Hirsch und ein schaukelndes Mädchen. Dahinter, mitten auf die Lichtung platziert, ein leerer Konferenztisch mit Stühlen, der ein leicht irritierendes Gefühl der Ortverschiebung erzeugt. Was hier erhellt, geklärt oder auch gelichtet wird, bleibt abzuwarten. Schrats Spiel mit kulturellen Topoi verweigert eine eindeutige Auflösung. Das Märchen von Sterntaler in zeitgenössischer Deutung? Märchen und Mythen sind schließlich nichts anderes als der Versuch, die Welt über das Erzählen von Geschichten zu verstehen und zu formen; Geschichten mit normativer Kraft, die essentielle menschliche Erfahrungen bildhaft vermitteln und als Speicher kultureller Erinnerung fungieren. Warenströme heißt ein Objekt, in dem eine ähnliche Verknüpfung der Ebenen stattfindet. Auch hier spielt sich das Geschehen im Wald ab, dem „anderen“, entrückten Ort der Verzauberung und Verwandlung im Märchen. Eine Gruppe von Leuten mit Säcken und Koffern wandert im Hintergrund über eine Lichtung und verschwindet wieder im Gebüsch. Schmuggler? Ali Baba und die vierzig Räuber? Eine Anspielung auf die mangelnde Transparenz von Produktbewegungen der globalen Märkte? Zwei Beobachter stehen im Vordergrund, verborgen im Unterholz: Hirsch und Hase sind hier zu Hause, und zum Zeichen der Gemütlichkeit hat sich der Hirsch eine Pfeife angesteckt. |

Silhouettes are developed as singular drawings or originate in murals. Often they are produced as cut-outs from plywood. They can be arranged on the wall as narrative particels of a larger context.

The text was first published in the 2005 Cataloge and refers explicitly to the shadow boxes.

The shadow is the sublation of the material condition of the body, and at the same time an indispensable reference to its existence. Already the bordered hand imprints of cave paintings from the stone age express the notion that the fixation of human contours, like an imprint of his or her physical presence, would keep the memory of the absent person better than any painted picture,.

For artists, the fascination of the silhouette today lies probably in the challenging openness of a form that oscillates between concreteness and ornament, abstraction and figuration, sharp limitation and an undetermined space, where the lack of information demands the beholder’s interpretation. Furthermore, silhouettes enable a kind of narration whose apparent harmlessness can quickly become a trap. Seduced by the pretty appearance of the surface in Kara Walker’s scenes for example, at first sight reminiscent of Biedermeier idylls, the beholder discovers monstrosities with which the African-American artist addresses ethnic, political, and sexual taboos.

Henrik Schrat’s shadows hide behind their surface not so much shocking moments, but rather a remarkably light-footed art of narration, characterised by ambiguity and cryptic humour. For a while now, he has been building large, box-like objects made of wood, similar to paper theatres, which heighten the narrative effect of his silhouettes and give them a stage-like quality. In Lichtung [‚Clearing‘], in a clearing in a pine forest, a belling stag and a girl on a swing meet, cutting diagonally across the foreground of the image. Behind that, placed in the middle of the clearing, an empty conference table with chairs, which creates a slightly disconcerting feeling of a geographical displacement. It remains to be seen whatever is being illuminated, clarified, or indeed cleared here. Schrat’s play with cultural topoi refuses a clear solution. The fairytale ‚Star Coins‘ in a contemporary interpretation? Fairy tales and myths are after all nothing more than the attempt to understand and form the world through the narration of stories; stories with a normative power that mediate essential human experiences in an emblematic way, and that function as a storehouse for human experience.

The artist is willing to divulge that what might be at issue in Lichtung is the lowering of costs and lean management. Often, Schrat’s fairytale-like scenes have titles that refer directly to events in the economy – a connection which in the case of Schrat is much more than just a superficial game with terminology. For years, he has been seriously addressing issues of the economy, management theory, and their connections to the art world. Not least, he co-edited an extensive reader on strategies in art and the economy.

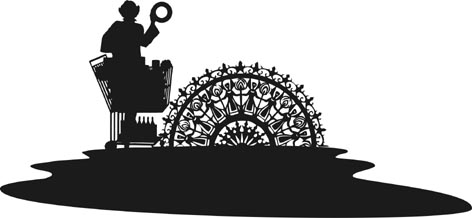

Warenströme [Commodity Flows] is the title of one object in which a similar connection of various levels takes place. Here, too, the events take place in the forest, the ‚other‘ place, the site of enchantments and transformations in the fairytale. A group of people with sacks and suitcases wanders in the background across a clearing and disappears behind bushes. Smugglers? Ali Baba and the forty thieves? A reference to the lacking transparency of commodity movements of global markets? Two observers stand in the foreground: stag and hare are at home here, and as a sign of Gemütlichkeit, the stag has lit a pipe.

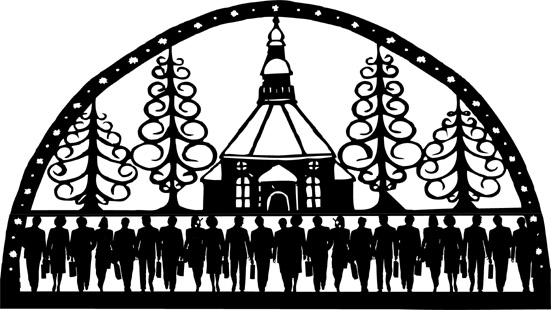

The humorous combination of differently connotated, often clichéd images and topoi is characteristic for Schrat’s way of proceeding. As models, he uses material from very different cultural contexts: motifs of folk art from the Erzgebirge und Vogtland, genre scenes by the nineteenth-century silhouette artist Luise Duttenhofer, English pattern-books of the 1970s, clip arts for graphic designers, corporate logos, his own drawings. The models are scanned, modified on the computer, moved about, cut, drawn over by hand, and finally cut in wood with the use of laser technology. Schrat’s production process corresponds to a contemporary form of silhouetting. Just as the object is reduced to its outline, the pixel image is reduced to a mathematical curve. Black allows for every combination, the images swallow each other and level the layers of space, time, and meaning from which they originate.

The forest in Markt consists of tree trunks which as it were lock off the space of the image; instead of leaves, they bear small corporate logos. An exhibitionist hides behind a tree. In his novel Der junge Mann, Botho Strauss describes the degenerate rituals of a post-capitalist society whose members vegetate in a decaying, half overgrown city. Of course this image, too, is only one possible layer of meaning. It is precisely the quick recognisability which gives contours as well as logos their direct effect, that in the end leads the beholder astray. Although the contour seems to refer to something clear, the possible meanings of the empty inner space are numerous. Schrat seduces us into a game with forms of cultural memories that collapse into each other in the shadow, as memory picture as well as projection screen, and spins old fairy tales further in a contemporary way: the economy as the production of myths, as a modern form of narrating the world, and explaining it.